Parga Castle

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

| Parga Castle | |

|---|---|

Κάστρο Πάργας | |

| Parga, Epirus | |

Parga Castle (2011) | |

| Coordinates | 39°16′59″N 20°23′51″E / 39.282999°N 20.397485°E |

| Type | hilltop[1] citadel |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Greek Ministry of Culture |

| Controlled by |

|

| Open to the public | Yes[1] |

| Condition | Ruin |

| Site history | |

| Built | Before 1390, 1808 (final stage) |

| Materials | hewn stone (ashlar) |

| Demolished | 1537 (rebuilt later) |

| Battles/wars | Ottoman siege (1452) |

| Events | Castle destroyed (1537) |

The Parga Castle (Greek: Κάστρο Πάργας) is a medieval hilltop[1] citadel complex in the town of Parga, Epirus, Greece. Located on the top of a hill overlooking the town, it has been an important landmark since the 15th century due in part to the strong fortifications used to protect the town from invasions from land and sea.

Location

[edit]Located on a strategically placed rocky peninsula overlooking the sea on three sides and the town on the forth.[1][2]

History

[edit]In antiquity the area around the castle was inhabited by the Greek tribe of the Thesprotians. The ancient town of Toryne was probably located here.[3] Before the strong castle of Parga was built (which survives today), the inhabitants of Parga[4] tried to keep the fortified city, which was exposed to the sea, so that they could face the invaders. In this effort, they built the first fortifications with the help of the Normans, initially in the 11th century by the residents of Parga to protect their town from pirates and later the Ottomans. In the 15th century, as Ottoman control of the region increased, the Venetians rebuilt the castle to fortify the area.

The town and its castle were unsuccessfully offered by Nicholas Orsini, the Despot of Epirus, to the Republic of Venice in exchange for Venetian aid against the Byzantine Empire.[5] During the Epirote rebellion of 1338/39 against the Byzantine emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos, Parga remained loyal to the emperor.[5] In the 1390s it was under the rule of Gjin Bua Shpata, lord of Arta.[5]

The town finally passed under Venetian control in 1401 and was administered as a mainland exclave of the Venetian possession of Corfu, under a castellan.[5] Venetian possession was confirmed in the Ottoman–Venetian treaty of 1419.[5] Apart from brief periods of Ottoman possession, the town remained in Venetian hands until the Fall of the Republic of Venice in 1797.[5]

In 1452, Parga and the fortified position was occupied by Hatzi Bey[6] for two years; part of the castle was demolished at that time. In 1537, Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa[7] burned and destroyed the fortress and the houses within. Before the castle's reconstruction in 1572 by the Venetians, the Turks again demolished it. The castle was rebuilt with the help of the Venetians, but before it was completed, it was demolished again by the Turks.

An inscription above the outer gate dates the construction of this section wall to 1707 by Count Marco Teotochi, governor and captain of Parga.[8]

In 1792, The Venetians began construction on the third and final fortress, with work being completed in 1808[9] by the French during their stay in the wider area between the years 1797 and 1814.[10] The castle remained invincible until 1819, despite the attacks mainly of Ali Pasha of Ioannina who besieged the castle.

In 1815, with French power failing, the citizens of Parga revolted against French rule and sought the protection of the British. In 1819, the British sold the city to Ali Pasha, under the broader authority of the Ottomans. Ali Pasha made structural additions to the castle, including strengthening the existing walls, installing his harem and building a hammams with the structure and radically remodelling the castle grounds.[4] In January 1822, Ali Pasha was assassinated, and from him, the castle passed under direct Ottoman rule.

Ottoman rule in Parga and the rest of Epirus ended in 1913 following the victory of Greece in the Balkan Wars[11] coming under the control of the Greek state.

In 2020 cleaning and restoration work was carried out by the Municipality and the Municipal Community of Parga under the supervision of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Preveza.[9]

Description

[edit]The Venetians created a perfect defence plan that, together with the natural fortification, made it an invincible fortress. Outside the castle, eight towers in various locations complemented the defence. Inside the narrow space of the citadel were stacked 400 houses, in such a way that they occupy a small space untouched by the sea.

From the fountain "Kremasma" the tanks of the castle and the houses were supplied with water. The castle, for its supply, used two bays: Valtos and Pogonia. The castle of Parga was invincible throughout the administration of Ali Pasha and offered great relief to the Souliotes who opposed it. In this castle, free besieged Parginians and Souliotes fought heroic battles and held their freedom for centuries.

The castle of Parga can be reached through narrow streets and stairs from the port of Parga, and there is a paved road that leads to the beach of Valtos. Provisions for the castle were transported via two bays at Valtos and Pogonia.

In the arched gate of the entrance, the winged lion of Saint Mark can be seen on the wall, the name "ANTONIO CERVASS 1764", emblems of Ali Pasha, two-headed eagles and related inscriptions.[12] Vaulted corridors, shooting rooms, supply arcades, strong bastions with firearms, light weapons, it is said that there is still a secret passage to the sea, barracks, prisons, warehouses and two forts on the last line of defence: they show perfection along with the plan they made the natural fortification an invincible fortress.[7]

An inscription above a stone door (adjacent to the powder magazine) reads: Défense de la Patrie Α.D. 1808.[10]

Current state

[edit]Today the castle is illuminated, and the public has the opportunity to visit it. In the central area, two main buildings have been reconstructed that host theatrical performances, exhibitions, and crowds. The Castle has a refreshment cafe, and an exhibition space where a photo exhibition is housed. The castle can be visited from early in the morning until late at night.[citation needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

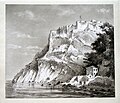

View of the castle of Parga, from a lithography of 1907, by Ludwig Salvator (1847-1914).

-

Depiction of the castle from a painting by Francesco Hayez (1791–1882).

-

Cannon along the walls 2015

-

Inside the walls of the castle 2011

-

View of the new town from the castle walls 2011

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Parga Castle". www.feelgreece.com. Retrieved Jan 10, 2023.

- ^ Castles of Northwest Greece: From the early Byzantine Period to the eve of the First World War, Allan Brooks pp207

- ^

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Toryne". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Toryne". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

- ^ a b "Venetian Castle in Parga, Greece | Greeka".

- ^ a b c d e f Soustal, Peter; Koder, Johannes (1981). Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 3: Nikopolis und Kephallēnia (in German). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-3-7001-0399-8.

- ^ "Πάργα". Retrieved Jan 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "Parga Greece, Parga Castle". Archived from the original on 2020-10-16.

- ^ Castles of Northwest Greece: From the early Byzantine Period to the eve of the First World War, Allan Brooks pp209

- ^ a b "Εργασίες Καθαρισμού Και Ανάδειξης Έφεραν Στο Φως "Κρυφές" Γωνιές Από Το Κάστρο Στο Νησάκι Της Πάργας - Parga News Πάργα | Η εφημερίδα της Πάργας". parganews.com. Mar 20, 2020. Retrieved Jan 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "Το Νησάκι της Παναγιάς στην Πάργα". onprevezanews.gr (in Greek). 2 August 2020. Retrieved Jan 10, 2023.

- ^ "History | ΔΗΜΟΣ ΠΑΡΓΑΣ : ΕΠΙΣΗΜΗ ΙΣΤΟΣΕΛΙΔΑ". www.parga.gr. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Castle of Parga | ΔΗΜΟΣ ΠΑΡΓΑΣ : ΕΠΙΣΗΜΗ ΙΣΤΟΣΕΛΙΔΑ". www.parga.gr. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011.

External links

[edit] Media related to Parga Castle at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Parga Castle at Wikimedia Commons